The Pickle Wars

Cucumbers, pushcarts and Bruekelen, oh my!

Once upon a time, the pickle vendors of the Lower East Side were both so numerous and ubiquitous that there was a street in the area nicknamed “Pickle Alley.” Eastern European Jews, who filled the tenements of the impoverished immigrant neighbourhood, sold pickles by the dozens from pushcarts on Essex street, until LaGuardia’s so-called “war on pushcarts” in the 1940s. But if you go to Essex street today, only one of these vendors remains: The Pickle Guys.

Something that many students of history do not necessarily understand is that for most of human history, humans were solely devoted to one enterprise: food. Even major empires like the Romans were so successful because they had created effective systems of distribution for food and water. When they collapsed, Europe moved towards the Feudal system, a system of agriculture and protection. Wars over bountiful lands shaped human history, from ancient battles over the fertile crescent to modern wars over the Ukraine. It wasn’t until the Industrial Revolution mechanized agriculture that we were able, as a species, to turn our greater attention to something other than food production and preservation, and thus modernize into the society of today. In a history of a species devoted to food, pickling played an important role, as it was able to preserve a wide variety of foodstuffs so to last through leaner months. The first known instance of pickling originated in vinegar-based brines in Mesopotamia. Dill, still immensely popular as an aromatic, arrived in the fertile crescent around 900 BCE. The Romans were more likely to prefer salt-based fermentation and brines, but both types remained in use throughout Europe and the Middle East. Before modern refrigeration, pickling and fermenting foods was central to the survival of our species.

When one thinks of the term “pickle” today, one really thinks of pickled cucumbers. Until I began researching for my interview with owner Alan, I was under the impression that these pickles were brought to New York by the floods of Central and Eastern European immigrants in the 18th and 19th century. After all, pickling of all kinds played a role in the cuisines of these areas. From sauerkraut to pickled cucumbers, from pickled herring to pickled eggs, the love of these foods run deep. But I learned something fascinating: it was actually the Dutch who brought pickling to the city, way back when it was still called New Amsterdam. Farmers would grow cucumbers on the big farms in Brooklyn (in Dutch, Bruekelen), and then steep them in salt water for preservation — indeed, the work “pickle” comes from the Dutch “pekel.”

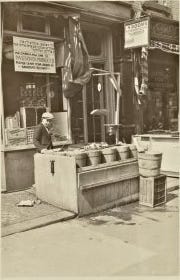

These cucumbers would be put in barrels of water so salty it may as well have come from the Dead Sea. Recipe books from the time period refer to the brine being “done” when an egg could float on the top. To this salty brine, different herbs and aromatics were added. While dill and garlic are perhaps the most well-known, whatever aromatics you added to the brine would then infuse the pickles themselves. Considering you might be eating your pickled vegetables all winter, you also wanted to make sure that they tasted good to you, so people got creative. These barrels were then put in the sun and left to ferment.

The Lower East Side practically overflowed with pickles in the 19th century, as Jews brought pickling methods and ingredients picked up in the shtetl to the new world. Once again, the pickle gained popularity as a food of poverty. Much like pickled herring or schmaltz herring, the pickle was ubiquitous because it was both cheap and healthy. It provided a great deal of nutrients, and was a lunch or snack fit for the frugal. Eastern European immigrants would push around carts with pickled cucumbers that would be sold for anywhere between one to five cents. Those who consumed a great amount of pickled vegetables also seemed to be “healthier” - although they didn’t really necessarily know the science behind that. It turns out that the salty brine makes the already-present vitamins and minerals stronger, particularly Vitamin C — one of the reason why Dutch sailors always seemed to get less scurvy than others.

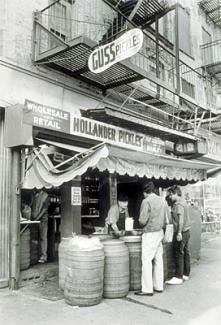

Much like the food truck wars that can play out in cities across the world today, where food trucks race for popular spots early in the morning or late at night, pickle vendors on Essex street used to be in active competition with each other. This tenacious competition didn’t exactly die out with the end of the pushcart era either. Take Guss’ pickles as the ultimate example. Guss’ pickles was founded by a Polish-Jewish immigrant in 1910, and one of the few that survived the economic ebbs and flows. But when it was sold, two families went ‘in’ on the Guss’ pickles trade together. When one wanted out and someone else bought it, in started a naming- and recipe-rights showdown that sounds like something out of Succession. In short, after multiple law suits & destroyed relationships, it was settled in 2009, and the purchaser was forced to give up the name Guss’ and now pickles under another name. The drama.

Now, if you go to the Lower East Side, only one pickle shop remains: The Pickle Guys, who are differentiated not only by historical continuity but also by recipe. Unlike the majority of North American pickle brands, which use vinegar-based brining, TPG continues to use the salt-based brines of the LES. This pickling process, also known as facto-fermentation, is used by them to pickle a whole host of things that the picklers of the early 20th century would never have gotten their hands on. But the most interesting part of the story, perhaps, is actually the backstory of the owner, Alan.

Alan Kaufman used to be a commercial advertising photographer, and he spent time on the Lower East Side with his portfolio. He would bring it to different places in the area, and while he was down there, he became friendly with a pickle vendor. This pickle vendor would not only feed him; as their relationship grew, he began to teach Alan the secrets of the old-school and old-world pickling. Since there was a lot of downtime between projects, he began working with him a couple of days a week. When said vendor started talking retirement, Alan realized that he not only enjoyed the work, but he had a real opportunity to save something historic and meaningful. He shuttered the photography business and went into pickling instead, maintaining the recipes and traditions that had been passed down to him. One of his biggest points of pride is that he has served three generations of one family. He’s also the only pickle vendor left in the area.

When you step into TPG, you’re simultaneously impressed with its simplicity and colour. It’s a storefront with multiple orange plastic (instead of wood, modernity is sometimes useful) barrels of pickles in the middle, filled with all sorts of different fruits and vegetables. From the bright picked onions to the spicy pickled pineapple, from half-sours to full-sours, from pickled garlic to baby corn, the offerings are many. I tried a number of them, and while I’m not actually a pickle person, I walked away with some half sours and pickled pineapple for our Shabbat table, generously provided by Alan. And even for a pickle-neutral person, the pineapples barely made it back to the dinner table because I couldn’t stop picking at them. The clientele was as diverse as the selection, from yeshiva bochers on their scooters to Asian tourists; by the time I left, the place was so packed I practically had to battle my way out. In case it’s not clear from the yeshiva bocher comment, it’s also strictly kosher. Alan’s motto seems to be that if you’re wondering whether or not something could be pickled, it probably has been - by him.

What struck me the most though is how much the old-world associations between pickles and health has taken on a whole new meaning. Apparently business is particularly brisk in marathon season. Trainers order gallons of brine for their runners, which they drink mid-marathon. Apparently the high salt content and lacto-fermentation helps keep them hydrated and cramp-free. People undergoing chemo also order brine from him, as drinking it appears to both settle the stomach and help them regain their appetite. While I have to be honest, imagining drinking salty pickle brine to help me through the nausea of chemo sounds … well, counterintuitive, there’s many who seem to disagree.

Alan describes his store as a living museum, and there’s something to that. There are very few opportunities in life to truly taste history, to eat something that is made in the same way, in the same place, as it was for your ancestors. To know that you’re eating a pickled cucumber that was first made this way in this place in the 17th century. To feel close to your ancestors who came here with nothing, and built food specific businesses because they only spoke yiddish and were living in grinding poverty and could do little else. To stand on Essex street eating a pickle that, were you to close your eyes, could have been being eaten by people in the same spot one hundred years previously; people who looked very different from you, but are perhaps not that different at all.

Betayavon!