The Bread of Seven Heavens, and Two Oblivions

Inviting a nearly twice-lost Shavuot recipe to your table

There’s this fun Jewish holiday at the beginning of summer, when my non-Jewish family groans “you have school off again!?” called Shavuot, which is a celebration of all things dairy. Ashkenazi Jewish digestive systems being what they are, often people are caught choking down Lactaid pills like they’re candy, preparing themselves for all of the cheesecake one can eat. But, most unfortunately, cheesecake and I have never seen eye-to-eye on its apparent deliciousness. So, I long ago started looking for alternative options that would satisfy the need for cheese, in a hopefully more carb-filled way. And this year, I want to introduce everyone to a recipe that should take front-and-centre on your tables, a recipe that was almost lost to history twice: the Sephardic bread, The Bread of Seven Heavens.

For those of you who don’t know, Sephardi Jews are those who can trace their lineage back to Spain and North Africa; this bread was aptly named El Pan de los Siete Cielos in Spain, and could refer to any of the many ways that the number seven signals a sense of wholeness or completion in Judaism in general. Shavuot falls seven weeks after the holiday of Passover, there are seven days of the week (the seventh day being one of rest), seven cycles of agriculture (wherein the 7th is a year of dormancy in Israel), seven days to Sukkot and Passover in Israel, seven blessings read at a wedding … you get it. I wonder if we can get credit for being the OG adaptors of “lucky number seven.”

Anyway, Jewish life in Spain was pretty awesome for a long time; at one point, a Jewish guy named Hisdai ibn Shaprut was Vizier to the Caliph (Islamic head of state) — like Jafar in Aladdin, although (hopefully) far less sinister.

It is thought that it was in this period that the Bread of Seven Heavens came into being, a reflection of the decorated and fruit-filled Easter breads commonly found on the Iberian Peninsula. Much like traditional Easter breads had decorations of the cross on them, this bread began to sport symbols of Judaism, such as Jacob’s ladder, Miriam’s well, and the 10 Commandments tablets. But hundreds of years later, and particularly after the Christian reconquest of Spain, Jewish status in Spain declined.

In 1391, there was a wide scale pogrom and Jews in Spain en masse were forced to convert by the sword. A generation or two later, Ferdinand and Isabella (the Spanish heads of state) were apparently concerned about the potential inadequate religious fervour held by converts who had been told that it was Christianity or death, and began the Spanish Inquisition. The Inquisition focused on these conversos, attempting to root out the private maintenance of Jewish faith — including by trying to hide pork in dishes that were then fed to conversos to see if they’d even flinch upon finding it. But that’s a bite-sized story for another day.

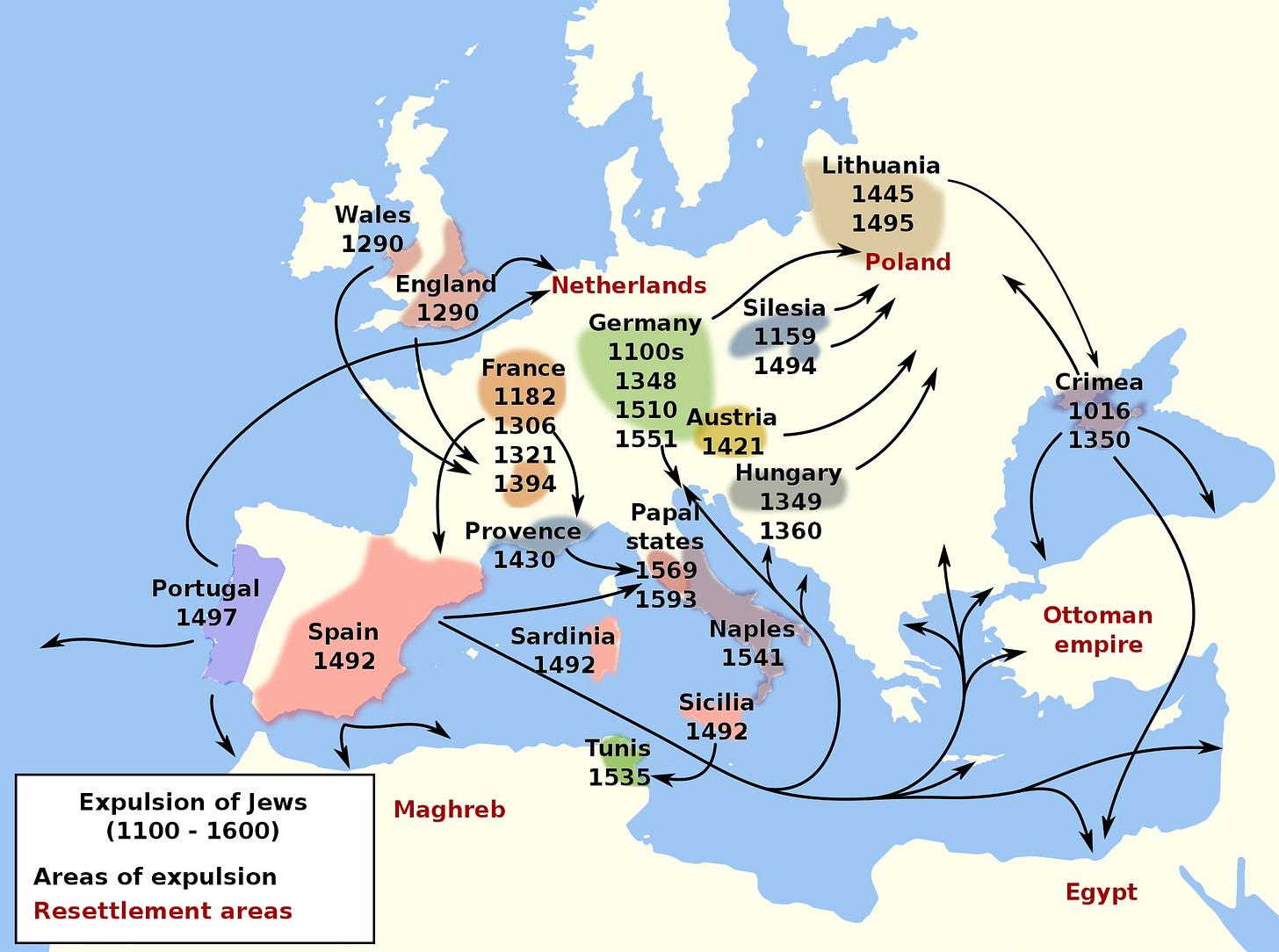

In 1492, attempting to ensure that the “new Christians” (former Jews) didn’t have any non-Christians to tempt them back down the path of Moses or whatever, the Jews of Spain were summarily given a couple of months to flee. And of course, they had to leave all of their non-portable (and most of their portable) wealth there with them. It’s always convenient when religious edicts also generates an “unexpected” financial windfall. While the c. 150,000 Jews forced to leave Spain spread all over Europe and the New World, a large number ended up in the Northern Greek town of Thessaloniki, or, Salonica.

The Bread of Seven Heavens barely survived this fundamental schism, but was soon reborn in a new city; by 1519, Sephardi Jews made up 54% of the city of Salonica, some 15,715 households. At this time, it was the only majority-Jewish city in the world. There, Shavuot traditions from Spain reconstituted themselves, although with different ingredients to hand, the former milk bread dough was now studded with oregano, feta, nuts and honey. Some people even espouse throwing a bit of Arak in the dough, just to really reinforce the anise flavour.

The bread can be made using an enriched dough (dough made with milk and eggs, my grandmother’s recipe below), and then rolled out into a long tube, and wrapped around itself seven times, culminating in a bread that is a bit mountain-shaped. Probably related to Mount Sinai, considering Shavuot commemorates the giving of the Torah at Sinai to Moses. (Note: once in Egypt, I forced my family to get up at the crack of dawn to go up Mount Sinai [none of them wanted to], and, dear reader, let’s just say that the question of Mount Sinai-themed bread may be deeply triggering to my dad and sister. I do not come off well in this story.) Anyway, once you have your mountain-shaped bread that does not at all invoke familial PTSD, it can (and should) be stuffed with your favourite toppings. Feel like commemorating the Jews in Spain? Soak some saffron strands in the water you use to the make the bread, and then stuff the concentric circles with manchego and dried figs. Thinking that the Grecian version may be more to your taste? Roasted garlic, brine-y feta, and fresh oregano is the way to go. And if you’re looking to get a bit daring? See if you can attach a small “Jacob’s ladder” up the side of the bread, reaching for its lofty heights.

I personally choose to make a Greek-themed version in honour of the community that this bread nearly died with. Salonica, the once only-majority Jewish city in Europe, struggled greatly in the nationalist conflicts of the early 20th century. In 1917, a massive fire swept through the city, leaving most of the Jewish community there unemployed. After Mussolini’s armies failed to take the area, Nazi forces swept into the country in 1941 to shore up its southern flank in advance of the assault on the Soviet Union. In July 1942, the Jews of Salonica were registered, and in March of 1943, they began to be deported en masse to Auschwitz. Only 4% survived.

Much like other places in Europe, all that you find now in Salonica is Jewish absence, in a place where Jews once lived, flourished and ate. But through recreating the food that they made, we can create an almost tangible link with them, as we reach our hands back in time to grasp their presence and lives before their destruction. Oh and also, it’s delicious. And for those of you who find the Ashkenazi-born tradition of cheesecake a bit unpalatable, perhaps it’s time to introduce a Sephardic one to your Shavuot table. Or at least to remember that this is a bread of a community born in Spain, forced to Greece, forced to Poland, and reconstituted in North America and Israel. And when we create it, we are inviting that history into our kitchen and our lives. Isn’t food great?

Betayavon and Chag Sameach!

My grandmother’s milk bread recipe:

Dissolve 1 package yeast in 1/4 c. warm water and 1 tsp sugar (let stand 10 minutes) in bowl of stand mixer.

Once yeast is puffed stir 2 eggs with 1 c. white sugar, 1 tsp. salt, 1/2 c. softened butter (1 stick), 2 c. lukewarm water.

Slowly add 6 c. of white flour, using the dough hook (never let it get above stir or “1”). Knead for 20m (if you’re stressed, you can do this by hand, it’s a great way to get out some aggression)

Let rise, pat down and rise again. Then shape into circular bread shape and add fillings of your choice

Let rise once more, brush with egg wash, and bake at 350 for 30m or until test knife comes out clean.

PS. Stay tuned for an interview with the great Adeena Sussman on her Shavuot table.