Garlic: Amulet or Aphrodisiac?

Looking at the strange and pungent relationship between Jews and garlic

Jews have a strange relationship with Christmas. There is both a desire to ignore it (movie/ Chinese food) and conflate Jewish holidays with it (Chanukah), but perhaps the strangest is a custom traditional to Medieval and early modern Central and Eastern Europe: Nittlenacht, aka “garlic eve,” the original Jewish observance of Christmas: eating enough garlic to repel a vampire.

But to back up to how Jews got there in the first place, let me tell you a bit about the Jewish relationship with garlic. Garlic is mentioned throughout Jewish literature, from the Torah to the Talmud, and in later Rabbinic writings. It was seen simultaneously as an amulet that could ward off “the evil eye” and an aphrodisiac. Yup, you read that right. Jewish men were encouraged to eat raw garlic on Friday nights to increase their virility, as traditionally marital relations took place on Shabbat — if you got pregnant on Shabbat, it was a double mitzvah! I mean, I’m not quire sure where “severe garlic breath” and “romantic vibes” intersect, but maybe that’s my modern sensibilities speaking.

In the Talmud, it went one step further. Garlic was seen as a “must-eat” for Jews, as it offered five benefits: it satisfied, it warmed the body, it caused one’s countenance to shine, it increased one’s sperm (sorry, ladies, I guess you only get four benefits) and it killed parasites in the intestines. (This wasn’t just a Talmudic thing; during the “Great Patriotic War” when Russian troops began running out of antibiotics, they used garlic in place of it — not sure how effective that was, but okay). It apparently could also be a salve for jealous spouses and cultivate “calmness” in them. Sephardic communities sometimes put garlic around a male newborn at a bris.

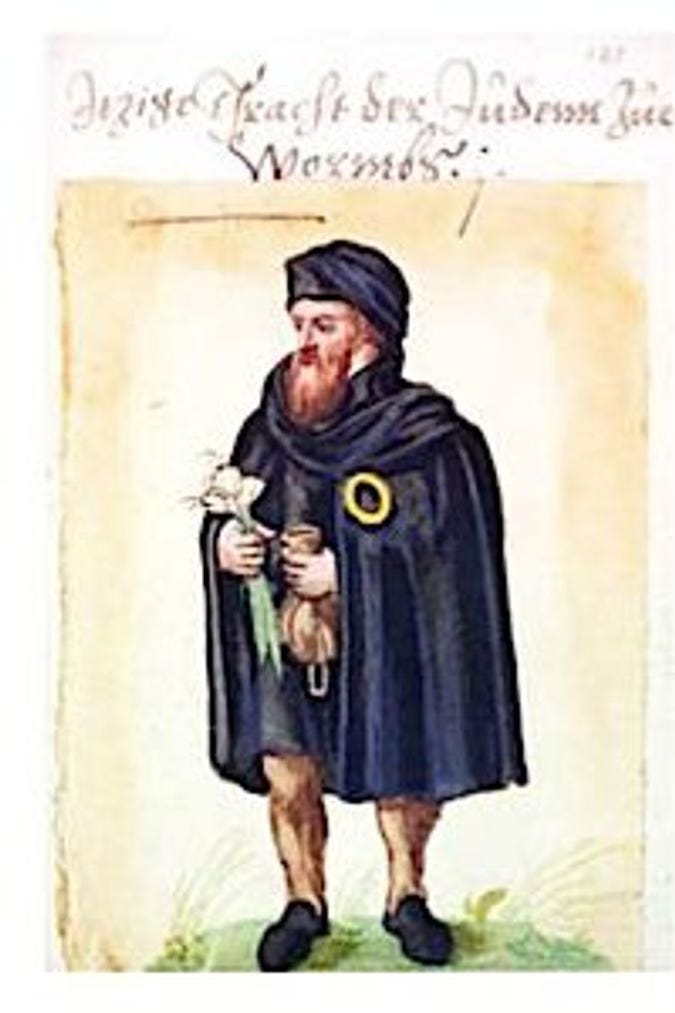

As Jews moved throughout the Diaspora, apparently garlic was one of the foods that always came with them. Even by Mediterranean standards, Jews were considered to be consumers of excessive amounts of garlic, and one of the ways that Jewish food tended to distinguish itself from Christian foods at the time was with the presence of fried garlic and onions. During the plague years, garlic became eaten feverishly and used as amulets in the desire to ward off disease. Not only were Jews apparently chowing down on raw garlic cloves as a way of mitigating the devastating effects of the “miasma,” they would hang bulbs of garlic outside of their doors as some sort of quasi-amulet of protection.

As I was researching this, I had a startling realization about a photo hanging on the stairs of my house that I took in Jerusalem some ten years ago — garlic hanging on the outside of doors in houses in Nachlaot, a neighbourhood near the central shuk in Jerusalem. I went down and examined it more fully, and I am torn between “traditional way to ‘avert the evil eye’” and “fresh garlic just purchased at the market that is being hung out to dry a bit.” Jury’s still out on that one.

Strangely, Jews did seem to get the Black Plague at a significantly lower rate than Christians, but this may have been due to more than just the garlic. Jewish law dictates a washing of hands regularly (before eating bread, after going the bathroom, before entering a synagogue, before and after you go to a graveyard etc.), and considering the traditional level of hygiene present in Medieval Europe, this automatically put them at an advantage. Even more so, Jews were often discouraged to touch others, were often segregated in ghettos away from Christian populations, and most importantly, by law buried their dead within a day. Christian law was not so strict about this, and countless people were ultimately infected from loved one’s bodies. Who knows, maybe the truly malodorous Jews of the period, replete with garlic breath, garlic oozing out of their pores, and garlands of garlic draped around their necks were so foul smelling that it kept others away from them, thereby actually reducing transmission rates. When Christians eventually realized that Jews were dying in significantly fewer numbers, they of course blamed Jews for causing the Black Death by poisoning the wells, and burned whole communities to the ground. No good deed goes unpunished.

But the smell of garlic soon came to be associated with Jews, often by people who were less than enamoured of them. The Romans derisively called the Jews “garlic eaters” (particularly Marcus Aurelius), and during the Spanish Inquisition, cooking with garlic could mean that you were identified as a “Jew” and was also seen as a way of “sussing out” crypto-Jews who were hiding their true religious convictions. In the Medieval period, Jews were described as having a specific Jewish stink that was garlic related, Foeter Judaicu. In the 18th and 19th centuries, antisemitic trinkets began to appear, porcelain Jews holding gigantic bulbs of garlic. Even the Nazis described them as having a distinctive garlicky smell.

But perhaps the strangest garlic custom was that of nittlenacht, a garlic-themed evening where Jews stayed at home, played cards, and ate garlic. Nittlenacht needs to be understood as the Jewish reaction to and rejection of the celebration of Christmas in Medieval Europe. Not only was Christmas often a time of greater physical danger for them, by this point in history, many Jews considered Jesus to be the bane of their existence. Jesus had been a Jewish man in the first century CE in Judea, one leader of the many Second Temple sects, who was into reforming Jewish law — in short, he was a rabble rouser, and traditionally, institutions don’t love that. He maybe wasn’t super popular with some Jews. But the Romans, being unable (or unwilling) to distinguish between religious and political leadership, crucified him. But within 30 years of Jesus’ death, a distinct religious identity with him at the centre began to emerge, which was viewed by many Jews of the time period with great hostility, particularly as the Christian Bible suddenly blamed the Jews for killing him. On a Roman cross. More on that later.

Partially the Jews on Christmas Eve stayed at home to avoid pogroms, which were common. They were not to read the Torah, and also very specifically not allowed to have sex. I know, I know, I said that garlic was an aphrodisiac and was supposed to encourage marital relations, but apparently it would be considered a great evil to have a baby conceived on the days that the Christians celebrated the birth of Jesus, whom the Jews did not think terribly highly of by this point. Indeed, there was actually covert literature read about Jesus by Jews on Nittlenacht, describing him as illegitimate and maybe someone capable of wielding black magic. Jews were, rightly, fairly terrified of the Church and the spirit of Jesus that governed all interactions with the Christians. One of the strangest writings on this came from an apostate, Johann Pfefferkorn, who wrote that Jews were also afraid of the latrine on Nittlenacht, as “demon Jesus” could reach out and pull them in. And, with garlic being the ultimate evil eye averter, what better to protect yourself from “demon Jesus” with? Boat loads of garlic. And thus Nittlenacht, or garlic eve, emerged.

Personally, I think that garlic is basically the life blood of every food. Our nanny regularly rolls her eyes when I get out 8 - 10 cloves of garlic for every meal. If you agree with me, check out this recipe for Toum, a Lebanese garlic sauce that is parve and delicious and adds acidity, brightness, and tang to whatever you want to slather it on. Which will be everything.

Toum:

Take 1 cup peeled garlic (fresh as you can find) and blend in a food processor

Slowly add a tablespoon of oil and wait as it blends in, before adding another. Once it started to emulsify, you can start the next step:

Slowly pour in one cup of oil, then 1/2 cup of lemon juice, and then another cup of oil. The emulsification of all three ingredients turn it into a white fluffy sauce. This will take about 15m.

Add salt, cover and put in fridge for 24 hours to set.

Enjoy on everything.

Betayavon!